Thursday: Gospel Mary

After drafting a blogpost early, I deleted it in total disinterest and made a spot decision not to blog today; I'd suit myself as I DWP, do some reading, play some online card games that I work for fun mental exercise instead of crossword puzzles. I might enjoy doing jigsaw puzzles as of old, but there isn't space here and I don't want to get into it. So, various card games of Solitaire, read, blog are my main things. Work up a Sunday School session if this is my week to lead the class, which it is not; or fiddle with a sermon if it's that week for me, which it is.

But today the decide was to give myself a break. Read, play Solitaire.

But then. One of my reading pastimes includes various blogs. Several from The Atlantic, although it's a royal pita to log onto them even though I'm a paid subscriber, leading me frequently to say to heck with it (anyone who knows me knows DW that I never say "heck").

Other blogs I enjoy are a few Bible scholars, university professors active or emeritus whom I admire. One whom I got onto recently through Bart Ehrman is James Daniel Tabor, his TABORBLOG, and this morning he posted a topic that ongoingly intrigues: all these Marys around Jesus in the gospels, and all these women anointing him while he's a guest for supper. With my highly sophisticated "yellow sticky note" thesis, I've long tied all these supper anointing events together as one event placed by each evangelist as best suits each one's agenda; but I'm still faced with all the Marys. Not the BVM, whom I greatly loved and admired in the film "The Passion of the Christ"; but Mary Magdalene, and Mary at supper, and Mary anointing Jesus' head and feet, and Mary at the cross, and Mary at the tomb, and Mary anointing Jesus' body. Plus, I'm of a mind that, Jesus being doctrinally fully human, he loved girls as much as the next guy (plus also totally open to some of the other reading between the lines implications of various evangelists); and over the years I've appreciated various non-canonical gospels, including Thomas, and Infancy Thomas, and Secret Mark, and Philip, and Matthew. In fact, I've not found it in every copy of Philip, but one copy either in my office or here at 7H, contains a delightful statement that at his baptism, Jesus came up out of the water laughing. And I fully appreciate Gospel Philip's referring to Mary Magdalene as Jesus' companion.

Anyway, TaborBlog in my email this morning takes up the subject of multiple Marys in the gospels, reasoning them as all one Mary. I won't do this in a sermon, but I would have taken it up as a really enjoyable Sunday School discussion.

Here's copy and pasted, Tabor's blogpost this morning. Enjoy!

RSF&PTL

T

sunset caught at StAndrews Marina yesterday, Wednesday, 18 May 2022

Was Mary Magdalene the same person as Mary of Bethany? A Guest Post from Jeffrey Bütz

Over the years I have written quite a bit about Mary Magdalene and her possible relationship to Mary of Bethany, sister of Martha and their brother Lazarus–who has a prominent role in the gospel of John (11:1-44; 12:1-8), is also mentioned once in Luke 10:38-42, but nowhere else in the New Testament. On the other hand, Mark (followed by Matthew), knows that Jesus and his entourage (the disciples, his mother and brothers) stay in Bethany the last week of his life–leading up to his crucifixion. One might well presume this is at the house of Lazarus and his two sisters, Mary and Martha. Mark also relates the story of a mysterious unnamed “woman” who anoints Jesus’ head with an alabaster flask of costly spikenard, also at Bethany that last week of Jesus’ life. In John it is clearly Mary of Bethany who does a similar (if not the same) anointing with spikenard–but of Jesus feet, wiping them with her hair. Quite oddly, Luke has his own anointing story, with an unnamed woman who is a “sinner,” who anoints Jesus feet, weeps, and dries them with her hair. But his account is much earlier in his gospel and seemingly nowhere near Bethany or Jerusalem (Luke 7:36-50).

So how can all this possibly be sorted out. How many times was Jesus “anointed” in such a scene–and by whom? And why does Mary of Bethany seem to just disappear from the scene after the anointing in John 12/Mark 14–whereas Mary Magdalene shows up so prominently at Jesus’ crucifixion and to anoint him after his burial? I have surveyed the evidence in my post “In Memory of Her: Mary’s Forgotten Memorial,” without really coming to any firm conclusion. I have also posted a guest entry by Jennifer Duba-Scanlan that was originally published in 2012 but is available here “The Mystery of the three Marys,” as well an earlier guest post from 2008 by Wendy Pond, based on an email she had sent me in response to my own posting, which you can read here: “Guest Post on Sorting out the Marys.” I highly recommend both these posts from these very insightful women. Just this week my friend and colleague, Jeffrey Bütz, shared with me a paper he has written arguing that Mary Magdalene is in fact the same person as Mary of Bethany–sister of Martha and their brother Lazarus. He has given me permission to post it here. Jeffrey is the author of two groundbreaking books that I highly recommend: The Brother of Jesus and the Lost Teachings of Christianity and The Secret Legacy of Jesus: The Judaic Teachings That Passed from James the Just to the Founding Fathers. Based on all this fascinating input I suppose it is about time I sort out my own evaluation and come to some conclusion. And in this case, it is not merely a matter of textual evidence, but also how our take on these various “Marys” might have impact on understanding the names we find in the Talpiot Jesus tomb–as well as ossuaries inscribed Mary, Martha, and Lazarus in the tomb complex on the Mt of Olives (on the Dominus Flevit property). More on that soon, but for now, here is Jeffrey’s paper:

MARY MAGDALENE = MARY OF BETHANY

The Case for Equivalency

The Rev. Jeffrey J. Bütz, M.Div., S.T.M.

For most of its existence, the Roman Catholic Church taught that Mary Magdalene and Mary of Bethany (sister of Martha and Lazarus) were one and the same person. This is often attributed to a sermon given by Pope Gregory the Great in the year 591 in which he asserted the two Mary’s were the same person, but this belief must certainly predate Gregory as we shall see. This identification became cemented in the General Roman Calendar, in which the Feast of Mary Magdalene (July 22) includes a collect referring to Mary of Bethany. There was no separate Feast Day in honor of Mary of Bethany until 1969 when the festival liturgy was revised and now Mary of Bethany is celebrated together with her sister Martha and brother Lazarus on July 29, reflecting the fact that the current interpretation of the Catholic Church is that these are two different women. This recent shift in understanding may have been influenced by the Eastern Orthodox and Protestant churches who have always held that these were different women. Today the vast majority of Christians hold to this shared assumption.

But does this common assumption really hold water? I would emphatically claim it does not. I, too, simply followed this commonly held belief until I recently visited pilgrimage sites in southwestern France where local Catholics firmly hold that Mary Magdalene and other family members lived in exile after fleeing persecution in Palestine. My personal pilgrimage there has caused me to radically re-evaluate some of my long-held assumptions. After looking deeper into the stories told of the two Mary’s in the gospels and other early Christian literature, I have become convinced they are one and the same person. When examined objectively, the textual evidence seems indisputable and I present that evidence here.

Let’s begin at the beginning with the earliest account we have (according to the “Marcan priority” view held by the vast majority of scholars). It is in Mark’s gospel that we first encounter Mary in the famous story of the “Anointing at Bethany.” There is a parallel account in Matthew’s gospel (26:6-13) which is almost word-for-word identical, making it clear that Matthew has simply borrowed Mark’s account. Here is the earlier account in Mark (14:3-9, NRSV):

3 While he was at Bethany in the house of Simon the leper, as he sat at the table, a woman came with an alabaster jar of very costly ointment of nard, and she broke open the jar and poured the ointment on his head. 4 But some were there who said to one another in anger, “Why was the ointment wasted in this way? 5 For this ointment could have been sold for more than three hundred denarii, and the money given to the poor.” And they scolded her. 6 But Jesus said, “Let her alone; why do you trouble her? She has performed a good service for me. 7 For you always have the poor with you, and you can show kindness to them whenever you wish; but you will not always have me. 8 She has done what she could; she has anointed my body beforehand for its burial. 9 Truly I tell you, wherever the good news is proclaimed in the whole world, what she has done will be told in remembrance of her.”

There are two things to note in Mark’s account. First, the woman who anoints Jesus is not named. If we only had Mark’s account, this woman would be forever anonymous. Why doesn’t Mark name her? There are two possibilities: Either Mark did not know her identity or he simply chose not to name her (as so many other women in the gospels go unnamed). Whatever the case, in Mark we have the first evidence of the possible equivalency of Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene: the anointing takes place in the town of Bethany (the home of the sisters Mary and Martha and their brother Lazarus) and an “alabaster jar” of ointment is used (which has become symbolic of Mary Magdalen in Christian art). We shall see further evidence for this when we examine John’s account. But first, let us look at another story of anointing by an anonymous woman as recorded by Luke (7:36-50 NRSV):

36 One of the Pharisees asked Jesus to eat with him, and he went into the Pharisee’s house and took his place at the table. 37 And a woman in the city, who was a sinner, having learned that he was eating in the Pharisee’s house, brought an alabaster jar of ointment. 38 She stood behind him at his feet, weeping, and began to bathe his feet with her tears and to dry them with her hair. Then she continued kissing his feet and anointing them with the ointment. 39 Now when the Pharisee who had invited him saw it, he said to himself, “If this man were a prophet, he would have known who and what kind of woman this is who is touching him—that she is a sinner.” 40 Jesus spoke up and said to him, “Simon, I have something to say to you.” “Teacher,” he replied, “speak.” 41 “A certain creditor had two debtors; one owed five hundred denarii, and the other fifty. 42 When they could not pay, he canceled the debts for both of them. Now which of them will love him more?” 43 Simon answered, “I suppose the one for whom he canceled the greater debt.” And Jesus said to him, “You have judged rightly.” 44 Then turning toward the woman, he said to Simon, “Do you see this woman? I entered your house; you gave me no water for my feet, but she has bathed my feet with her tears and dried them with her hair. 45 You gave me no kiss, but from the time I came in she has not stopped kissing my feet. 46 You did not anoint my head with oil, but she has anointed my feet with ointment. 47 Therefore, I tell you, her sins, which were many, have been forgiven; hence she has shown great love. But the one to whom little is forgiven, loves little.” 48 Then he said to her, “Your sins are forgiven.” 49 But those who were at the table with him began to say among themselves, “Who is this who even forgives sins?” 50 And he said to the woman, “Your faith has saved you; go in peace.”

The first question that must be asked is this: Is Luke’s account recording the same event as Mark, or is this a second instance of an unnamed woman anointing Jesus from an alabaster jar? One of the points favoring the latter interpretation is that this woman anoints Jesus’ feet, while in Mark’s account it is his head that is anointed. Also, Luke’s account takes place in the home of a Pharisee, while Mark’s account is in the home of “Simon the leper.” This has led some scholars to assume these were two different events, or at least two different traditions received independently by Mark and Luke. Luke’s account takes place in Galilee early in Jesus’ ministry, while the accounts in Mark and John take place in Bethany during the last week of Jesus’ ministry just prior to Passover. So, on the surface it would appear that these are two different events.

However, despite these differences in time and place, there is one striking similarity between Mark and Luke. In both accounts an anonymous woman just suddenly appears out of nowhere and anoints Jesus. This is most unusual. And it seems highly unlikely that two different anonymous women would have done this on two different occasions (and in two different houses of a man named Simon). The most likely explanations are that Luke either received this tradition in a different form than what Mark had (from his unique “L source,” according to what scholars call the Two-Document Theory), or Luke had theological reasons for changing the setting of the tradition he found in Mark. It is the latter that seems most logical as I shall now explain.

One of the most striking differences in Luke is that specifically points out that this woman was a “sinner” which Mark does not (nor John as we shall see). There are a couple possible reasons for Luke doing this. One may be to enable him to use this story as an exemplar of Jesus’ authority to forgive sins. Supporting this is the fact that the mini-parable Jesus tells, known as the “Parable of the Two Debtors” is found in no other gospel. Another possible motive is that Luke wants to explain why a woman would dare to touch a man to whom she was not married, a great sin according to Jewish law. Both of these reasons were likely in play for Luke. Supporting this is the other glaring difference in Luke’s account—this woman anoints Jesus’ feet, not his head. In Mark’s account, after the woman anoints Jesus’ head, he says, “she has anointed my body beforehand for its burial.” In removing the anointing from the context of burial, Luke offers a more practical explanation for the anointing. The woman washes and anoints Jesus’ feet as a servant would normally do as a matter of formal protocol when a guest visited a home (and Jesus pointedly disparages Simon the Pharisee for failing to do this). And there is one more piece of evidence for Luke’s intentional rearrangement of Mark’s account. According to Catholic scholar Robert Karris,

“He has set the tradition within the framework of a Hellenistic symposium genre, which he employs also in 11:37-54 and 14:1-24. The dramatis personae of this genre are host, chief guest, and other guests. The structure is invitation (v 36), gradual revelation of who the host (v 40) and other guests (v 49) are, the fait divers or action that prompts the speech of the chief guest (v 39, Simon’s unspoken reaction), and the speech of the chief guest (vv. 40-50).” [1]

It is enlightening to note that it is only in Luke’s gospel that Jesus eats in the home of a Pharisee, and does so on three occasions! It seems quite clear that Luke has taken Mark’s story and edited it for his own theological purposes. Thus, we can leave aside Luke’s account in trying to determine the actual historicity of the anointing story.

Let us move on then to the account in the Gospel of John which is much more enlightening as the actual historicity of this anointing (John 12:1-7 NRSV):

Six days before the Passover Jesus came to Bethany, the home of Lazarus, whom he had raised from the dead. 2 There they gave a dinner for him. Martha served, and Lazarus was one of those at the table with him. 3 Mary took a pound of costly perfume made of pure nard, anointed Jesus’ feet, and wiped them with her hair. The house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume. 4 But Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples (the one who was about to betray him), said, 5 “Why was this perfume not sold for three hundred denarii and the money given to the poor?” 6 (He said this not because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief; he kept the common purse and used to steal what was put into it.) 7 Jesus said, “Leave her alone. She bought it so that she might keep it for the day of my burial.”

We immediately see that this account is much more in line with the account in Mark. Both the time-frame (just prior to Passover) and the locale (Bethany) are identical. Only the specific location differs—the house of Simon the Leper in Mark, and the home of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus in John. Despite this difference, as we saw earlier, it is very difficult to believe that Mark and John record two different events. We are now left with only two possibilities regarding this singular anointing: Either John has changed the location, perhaps using a different account from the tradition found in Mark, or John’s account is the most accurate. There are very good reasons for favoring the latter. Dr. James Tabor has shown that in so many instances where John differs from the synoptic gospels, John has corrected the earlier tradition with better historical information. [2] This can be seen here, in that John differs from Mark in one other detail: He agrees with Luke against Mark that Mary anoints the feet of Jesus not his head. John also agrees with Luke that she wiped his feet with her hair. As we saw, it is this highly controversial act that impelled Luke to deem this woman a sinner. But in John, as in Mark, this act is interpreted as a preparation for Jesus’ burial. John is clearly correcting both Mark and Luke. And it is in John’s identification of Mary of Bethany as the woman who does the anointing in preparation for Jesus’ burial that we have the primary evidence that Mary of Bethany is in fact Mary Magdalene. As Catholic scholar, Hugh Pope noted over a century ago in the Catholic Encyclopedia:

“Is it credible, in view of all this, that this Mary [Mary of Bethany] should have no place at the foot of the cross, nor at the tomb of Christ? And yet it is Mary Magdalen who, according to all the Evangelists, stood at the foot of the cross and assisted at the entombment and was the first recorded witness of the resurrection. And while John calls her ‘Mary Magdalen’ in 19:25, 20:1, and 20:18, he calls her simply ‘Mary’ in 20:112 and 20:16.” [3]

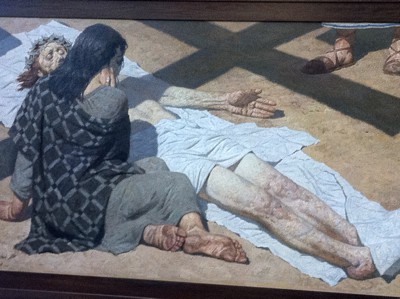

Indeed, why would Mary of Bethany, who Jesus says (in Mark), “anointed my body beforehand for its burial” and who Jesus says (in John) bought the ointment, “so that she might keep it for the day of my burial” not be at the tomb to complete what she had begun? According to all four gospels a woman name Mary was at the tomb to do just that. And this woman is called Mary Magdalene. My thesis that Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene are one and the same person resolves all the discrepancies in the gospels. But, there is just one other major question to resolve, the “elephant in the room” at Bethany: Why would Mary be allowed to touch Jesus in such an intimate way in public, and also be the one to prepare his body for burial after the crucifixion (which also involves intimate touching)? To answer that means opening a huge can of worms best left for another day!

I would like to end with one further piece of evidence for the equivalency of Mary of Bethany and the Magdalene by citing the so-called “Secret Gospel of Mark,” which a number of scholars (including Helmut Koester, Marvin Meyer, and John Dominic Crossan) believe is an earlier version of Mark (of which canonical Mark is an abbreviated version). We only have two extant passages from Secret Mark preserved in the “Mar Saba Letter,” believed by a majority of scholars to have been written by Clement of Alexandria. One of those passages is the story of the raising of Lazarus (found only in John’s gospel) and its inclusion in Secret Mark is evidence that John must have known the earlier and longer “Secret Mark.” According to Clement the following was originally found between Mark 10:34 and 10:35:

And they come into Bethany. And a certain woman whose brother had died was there. And, coming, she prostrated herself before Jesus and says to him, “Son of David, have mercy on me.” But the disciples rebuked her. And Jesus, being angered, went off with her into the garden where the tomb was, and straightway a great cry was heard from the tomb. And going near Jesus rolled away the stone from the door of the tomb. And straightway, going in where the youth was, he stretched forth his hand and raised him, seizing his hand. But the youth, looking upon him, loved him and began to beseech him that he might be with him. And going out of the tomb they came into the house of the youth, for he was rich.

The one other passage Clement cites, he says was originally part of Mark 10:46: ” . . . after the words, ‘And he comes into Jericho’ the secret Gospel adds . . . ‘And the sister of the youth whom Jesus loved and his mother and Salome were there, and Jesus did not receive them.’” There are two things of note here that add further evidence to our theory of equivalency. The first is the statement: “And the sister of the youth whom Jesus loved and his mother and Salome were there.” This is most striking for the “youth whom Jesus loved” is obviously Lazarus and his sister is obviously Mary of Bethany. What significant is that according to Mark’s gospel the three women who went to the tomb to anoint the body of Jesus were “Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome” (Mark16:1). “Mary the mother of James” is certainly referring to the mother of Jesus, for James was Jesus’ brother. Salome is either the sister of Jesus or the sister of his mother. This is backed up by the gnostic Gospel of Philip, which in verse 32 says, “There were three who walked with the Lord: Mary his mother, and his mother’s sister, and Miriam Magdalen, known as his companion . . .”

We shall not even begin to delved here into the current controversy over the meaning of “companion”! But there is one final thing of note. The prior quote from Clement says that the youth whom Jesus raised was rich. This becomes significant when we look at this passage from Luke (8:1-3 NIV):

After this, Jesus traveled about from one town and village to another, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God. The Twelve were with him, and also some women who had been cured of evil spirits and diseases: Mary (called Magdalene) from whom seven demons had come out; Joanna the wife of Chuza, the manager of Herod’s household; Susanna; and many others. These women were helping to support them out of their own means.This passage attests that some of Jesus’ female followers were wealthy and financed Jesus’ ministry. Joanna is the wife of King Herod’ household manager! And this passage intimates that Mary Magdalene was wealthy. And we learn from “Secret Mark” that Mary of Bethany was wealthy.

In summary, we have a wealth of information that when put together all points to one conclusion. The Roman Catholic Church had it right from the beginning. Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene are one.